What can photography do for a world that came? A commentary on “For A New World To Come: Experiments in Japanese Art and Photography, 1968-1979”.

What can photography as a field and photographers say about the time and place they live in? This is not the central question the exhibition ponders, but rather it is a question that connects the social and political context in which Japanese photography developed betweek 1968 and 1979, and that of the world nowadays. The Japanese artists and photographers whose works and ideas are depicted in this exhibition are preoccupied with the particular sociocultural setting of their time, just after the political struggles of student protests, the social climate of distrust by the Japanese Left and the masses in the face of a rapidly changing social, political and economic climate of the Japan of the 1970s. What can this tell us about our seemingly very different contemporary world?

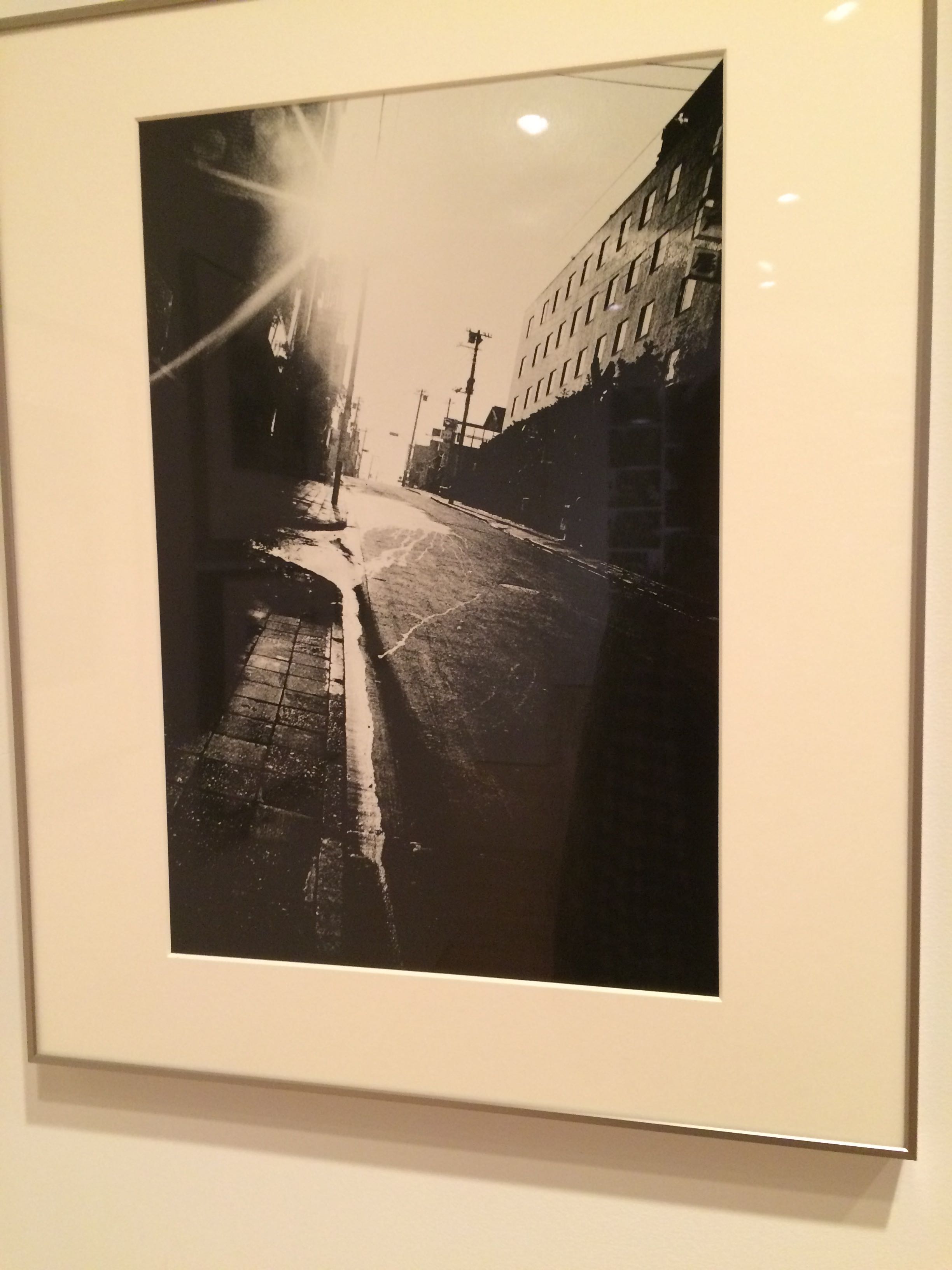

When we think about Japanese photography of that era many may associate it with the aesthetics of the magazine Provoke (the aesthetics of “Are, bure, boke”): high contrast, out of focus, grainy black and white images, made famous by the works of photographers such as Daido Moriyama or Takuma Nakahira in the late 1960s. However, there is more to the story. As the introduction to the exhibition points out, photography became the medium through which both the highs and lows of political and social unrest were documented in a rapidly changing sociopolitical landscape. On the one hand, the protest and political unrest in Japan reached its mass peak in the final years of the 1960s, but after 1970 much of the previous activism turned into political apathy. Using the medium of photography, artists and photographers (if they are not the same thing) reimagined the impact that visual media had in Japanese society. The aesthetics of Provoke were a response to what politics and discourse apparently could not do; what Nakahira himself meant when he wrote: “Today, when words are torn from their material base-in other words, there reality-and seen suspended in space, a photographer's eye can capture fragments of reality that cannot be expressed in language as it is.” What Nakahira was calling for was a new relationship between images and language. This is, according to him, the power of the image: to be able to say something about everyday reality that cannot be fully conveyed through discourse and politics. This is particularly poignant in a social context of political apathy and disillusionment, like it was in the Japan of the 1970s. Photography, influenced by the collaborators to Provoke and those in this exhibition, became a new language of dissent and expression for new ideas and for engaging with this sociohistorical context.

Now, what if you are not interested in the history of Japan (or the world) in the late 1960s and 1970s? Can this exhibition and its subject matter say something that is not just a historical case-study? I think the merit of presenting an exhibition like this, 40-something years after the fact, is that the current world is actually going through a very similar process to that which Japanese society was going through at that time. In the years between the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, Japanese photography developed in a context of social, political and economic uncertainty. In that sense, photography became the medium of politics “par excellence,” even if much of the work many Japanese artists and photographers did never intended to be openly political. Currently in the United States and the Western world there is much distrust in politics. Not many want to enter the political game or participate in traditional politics (this is particularly evident in low voting turnout, lack of participation in electoral institutions, reluctance to talk about politics, etc.). That being said, that does not mean that people are not very political in the sense that they are preoccupied with complex issues that impact their everyday lives (such as safety and security, immigration, the environment, job security, the economy, etc.). In that sense, even if not through the “language of politics,” people are active in a kind of “politics of everyday life,” or “politics of small things” that is particularly obvious precisely in people’s apathy towards what is usually understood as “politics.” (the big language, institutions, electoral campaigns, support for politicians). The fact that we worry about the state of the world we live in shows precisely our engagement with the world surrounding us. This type of politics is what photographers such as Takuma Nakahira, Daido Moriyama, Eikoh Hosoe, Keizo Kitajima, etc. gave a language to during the time frame this exhibition depicts.

Another unlikely important similarity between then and now is the apparent diminishing importance of images in a world where they are everywhere, and where –in their ubiquity—they have lost their critical meaning and punch. Whereas images of the poor and hungry (or the images of luxurious lifestyles depicted in advertisements) have been normalized, and where images are produced (and shared online) by the thousands every minute all around the world, some images still do speak personally to us. Think of the image of the drowned body of the Syrian refugee child washed ashore that sparked the conversation about refugee rights in Europe a few months ago. In the Japan of the late 1960s and 1970s, visual culture abounded due to new technical capabilities (the wide availability of television, advertisements, printed media, etc.) and the economy that supported it. Images were ubiquituous in Japan then, and the meanings were also normalized. Images were a “spectacle” without very little possibility of critical engagement. In such a context, the photographers whose work is presented in the exhibition created an aesthetic language that could say the “unsayable” in known political language… they used photography as a medium to say something important.

In that sense, this proves the point that there are lessons to be learned about the language that art can provide; Art and photography can create new forms of political engagement and imagination “for the world to come.” It is often not the case that people are not preoccupied with the world. Nakahira, Moriyama and others said something important through their photography. What exactly? This is debatable and oftentimes different depending on the artists, but at least their images opened the possibility of a conversation and critical engagement with the world and its complex problems. In that sense, photography in this historical moment of Japanese society is very much like various forms of socially engaged art being done nowadays (such as that being done by artists such as Theaster Gates, Rick Lowe, Jon Rubin, etc.), providing a way of imagining how to do something in the face of not being able to do anything due to the extremely complex and difficult problems the people of contemporary global societies are facing.

Photography and art are not just representations of a particular time and place. They are languages and poetics through which people (artists, viewers and participants) can understand and engage with the politics of everyday life in a significant manner. If there is a big virtue to that, it is that, in fact, this type of engagement (poetic and ideal as it might be) does something to people. It makes individuals think about the world in a more critical manner, which is something that cannot even begin to occur when people simply understand themselves as being powerless in the face of the complex systems of power, economics, state and capital institutions.

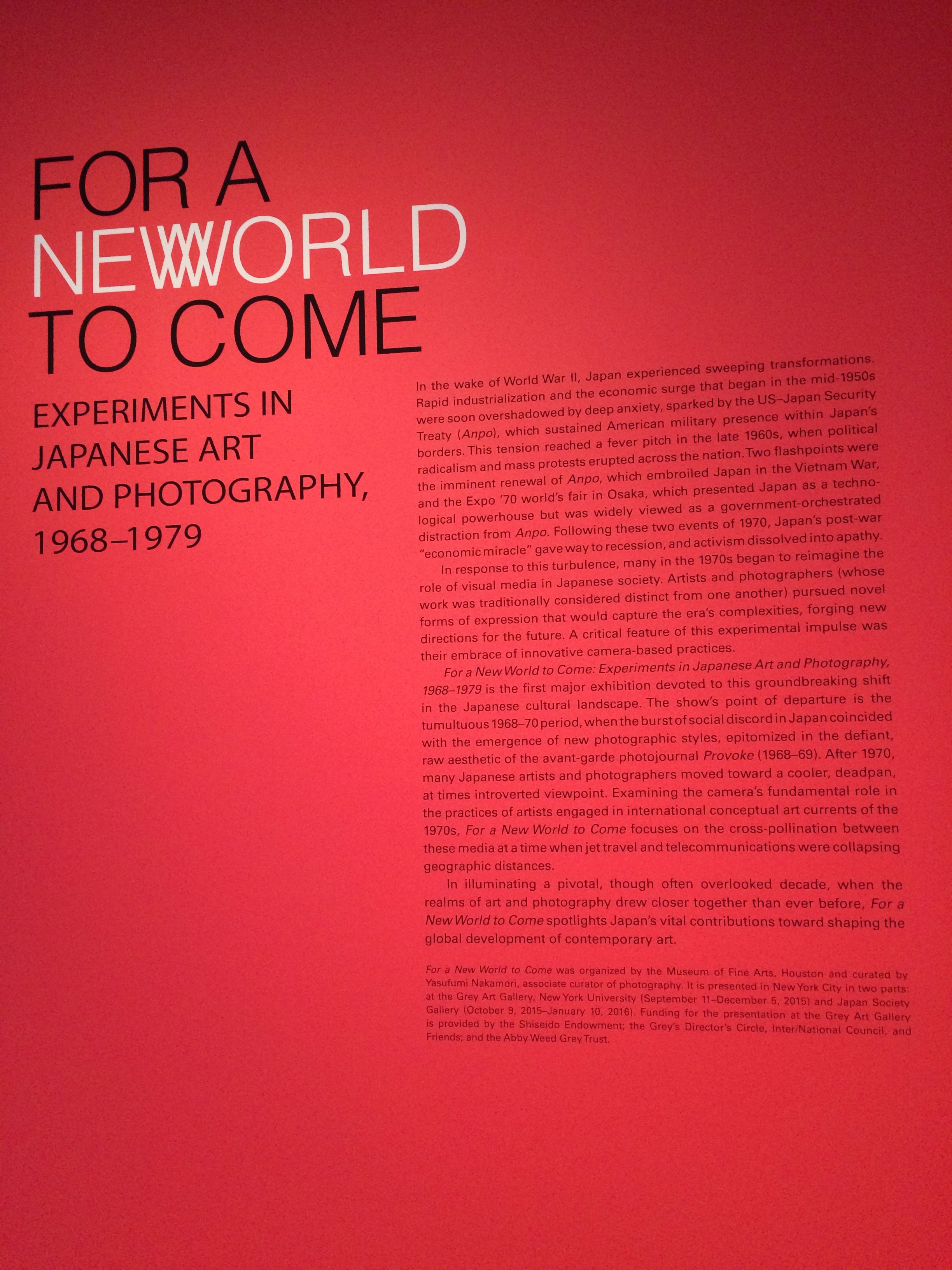

For a New World To Come: Experiments in Japanese Art and Photography, 1968-1979. Organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and curated by Yasufumi Nakamori, associate curator of photography.

On view in New York City at the Japan Society Gallery (October 9, 2015 through January 10, 2016) and Grey Art Gallery, New York University (September 11 through December 5, 2015). http://www.japansociety.org/page/programs/gallery/for-a-new-world-to-come